How to Improve Your Whiteboard Coding Interview Skill

Posted on Mon, 18 Oct 2021 in Other

In the last couple of years, I have conducted more than 30 job interviews: on-side whiteboard interviews and, because of Covid, Skype interviews. I saw candidates with different skills. I saw two superstars of whiteboard coding. I saw many guys who thought that they can code, but weren’t able to write a single line or tell for from while. But these are corner cases. What about a regular guy with enough skill and knowledge for the job but not so experienced in whiteboard programming? Like me. I have given much fewer interviews than I have taken. So I am a junior in whiteboard coding.

As an interviewer, however, I can give you one piece of advice that will double your chances to get a job. Here is my tip: Write down every state of each variable in your code during a whiteboard interview. That is it. You can stop watching here. I have already given you the main idea of this video. For the rest of it, I am going to explain why it is so important and how to develop that skill.

Why is it so important? A sad story about why we have to code on a whiteboard...

If you ask me, a coding interview is a waste of time. As a candidate, you have to show skills that don’t require for a position you want to get. As an interviewer, you ask people to solve problems that have nothing to do with the real world and make them struggle to balance a Red-Black tree... But there is a company. From its point of view, a whiteboard interview is not a bad thing.

Companies want to hire someone to fill the position. They want to hire someone as soon as possible. But costs of hiring the wrong person are much higher than the costs of missing the right one. To fit corporate processes, the method should be quite cheap and highly scalable. And it should filter out as many wrong persons as possible. As a result, we have to have that stupidly long series of coding interviews (Stupidly long is more than one).

Whiteboard coding is one of many options. There are challenges for homework, a day of work in a team on real-world tasks to name a few. These methods are better ways to choose a developer. But coding interviews are much cheaper and they work quite well. They filter out candidates who can’t code at all.

But because its efficiency is far from ideal, companies tend to chain coding interviews. The bigger the company the more chances there are several whiteboard coding interviews. In today's industry, the only chance to avoid this kind of interview is being a superstar developer who is trying to find a job in a small company.

Failure Rate

From my experience, only one of 8 candidates successfully performed during the interview. At least two candidates out of the 8 who failed had a chance to do their interview well. Why is the rate so low? I have analyzed many interviews to find a pattern that leads a candidate to success. But first of all, let's look at why candidates fail.

The main reason is that candidate has no coding skills. Unfortunately, it happens often. The stronger the HR brand of the company the more often it happens. Usually, candidates from that category have no chance to get an offer. Usually, they can't write a line of code. The second reason for failure is a candidate's inability to debug their code on a whiteboard. All candidates who performed well, especially superstars, all debug their code.

I’ll show you a couple of scenarios on how I as a candidate can debug my code. From the worst to the best.

The worst scenario is quite short.

Me: “It looks OK”

Interviewer: “No. There are bugs”

Some random changes in the code…

Me: “Is it OK now?”

Interviewer: “No…”

Usually, there is one more iteration of this… discussion. As a result, the reviewer texts an HR “No hire”. This scenario is quite common. Often it happens when a candidate is in a hurry or a task is too complicated. The best outcome from this interview is not an offer, but a chance to have another attempt in 6 months or a year. So maybe there is a better strategy than just saying nothing?

The next scenario is better although far from the ideal.

The candidate debugs the code but writes nothing down. For an interviewer, it is extremely difficult to follow a candidate’s thoughts. And it is error-prone. From my experience mistakes that candidate makes in the debug stage ruin the whole interview more often than a code full of bugs. Sometimes it looks like a joke.

Once I took an interview with one guy. I gave him a problem. He wrote a decent code. Few bugs, nothing special. He started debugging. He wrote nothing down. He made a mistake once. If I remember it right, he forgot the previous value of an index. First strike. He made a mistake again. Again something with indexes. Second strike. Finally, he solved the problem. I gave him the next problem to solve. Again he wrote a decent code with little help. He knew how to code. Debugging stage…

The candidate started going through his code using a test case from the description of the problem. It was a long test case. He had to go 9 times through the cycle in the code. It required a lot of time. Of course, he stopped after 3 iterations saying “It works”. No, it didn’t. There was a bug in the first line of the cycle and the very next step would show it. But… No hire!

Anyway, a couple of times candidates passed their interviews with that style of debugging. No one passed the next stage with a bit more advanced tasks.

In the third scenario, you write down every state of each variable in your code during debugging. Again it is the story from my experience. A candidate less experienced in coding than the previous one wrote a code full of bugs. However, during debugging he wrote everything down. Every value of each variable was on the board. As a result, he found all bugs in his code. And did it quite fast.

Example

What did he do? To illustrate that I will solve a simple programming problem. Let’s assume that I am a candidate and I was asked to solve the Counting Valleys from HackerRank.

An avid hiker keeps meticulous records of their hikes. During the last hike that took exactly steps, for every step, it was noted if it was an uphill, or a downhill, step. Hikes always start and end at sea level, and each step up or down represents a unit change in altitude. We define the following terms:

A mountain is a sequence of consecutive steps above sea level, starting with a step up from sea level and ending with a step down to sea level.

A valley is a sequence of consecutive steps below sea level, starting with a step down from sea level and ending with a step up to sea level.

Given the sequence of up and down steps during a hike, find and print the number of valleys walked through.

There are two sample inputs.

assert counting_valleys('UDDDUDUU') == 1

assert counting_valleys('DDUUDDUDUUUD') == 2

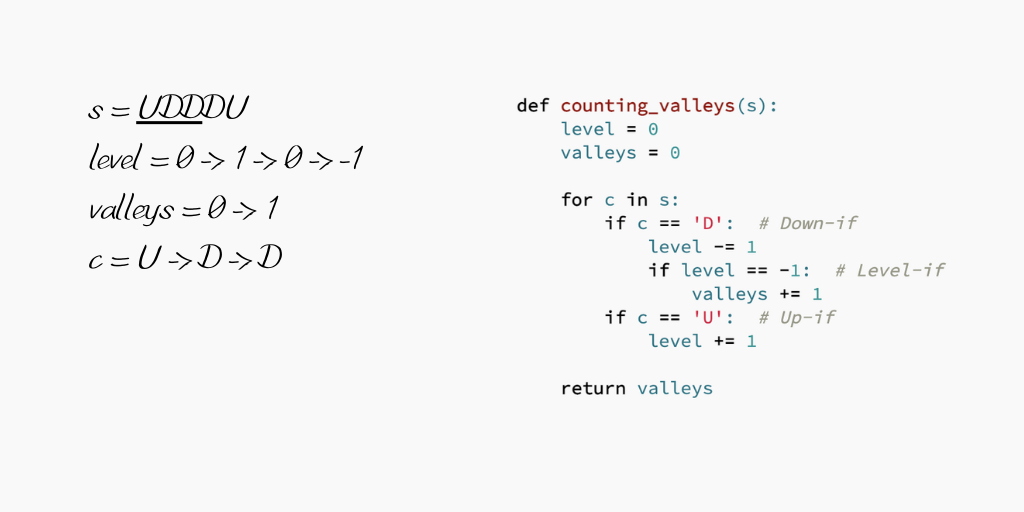

After a while, I wrote this code. Probably, there are some bugs in this code. During an interview, I will assume that I always write with bugs.

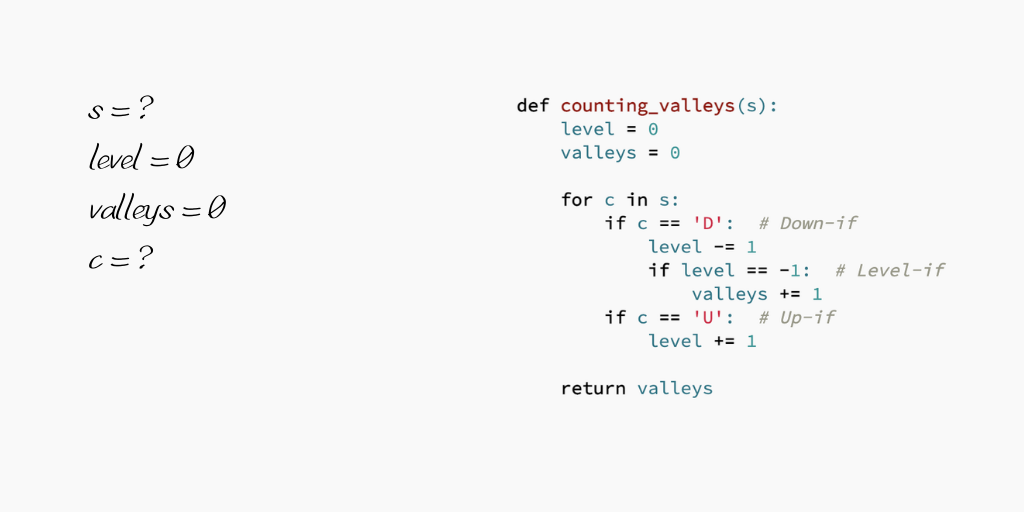

def counting_valleys(s):

level = 0

valleys = 0

for c in s:

if c == 'D': # Down-if

level -= 1

if level == -1: # Level-if

valleys += 1

if c == 'U': # Up-if

level += 1

return valleys

First of all, I will write down all variable names from the code in the list near it.

It is wise to prepare a couple of test cases in advance that is short and cover all corner cases. But it is a topic for a different discussion. I have prepared one. It is a bad test case. I would prefer a shorter one. I made it longer than necessary to illustrate the process.

Let’s go

assert counting_valleys('UDDDU') == 0

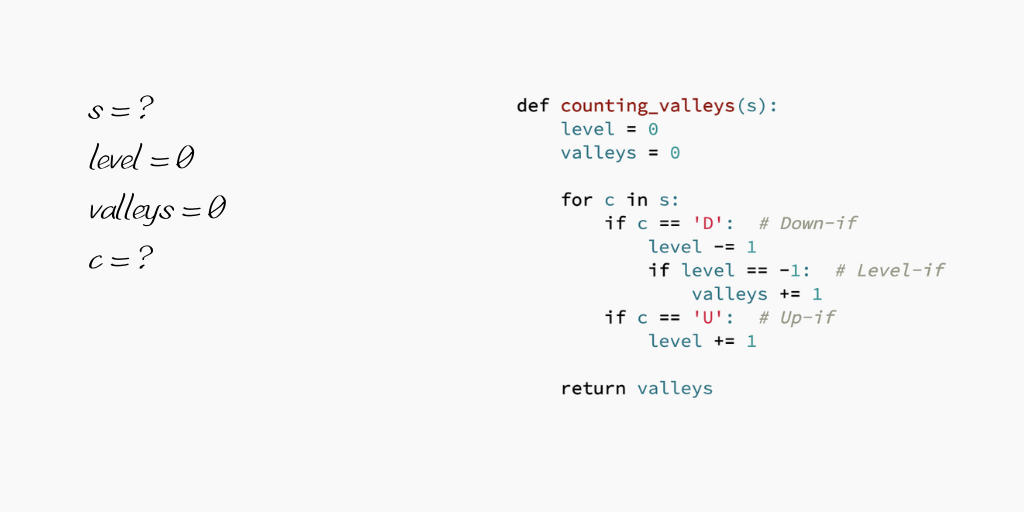

So s is equal to UDDDU

level and valleys are equal to 0

The cycle will be evaluated because s is not empty

c is equal to U. I will underline the first U in s.

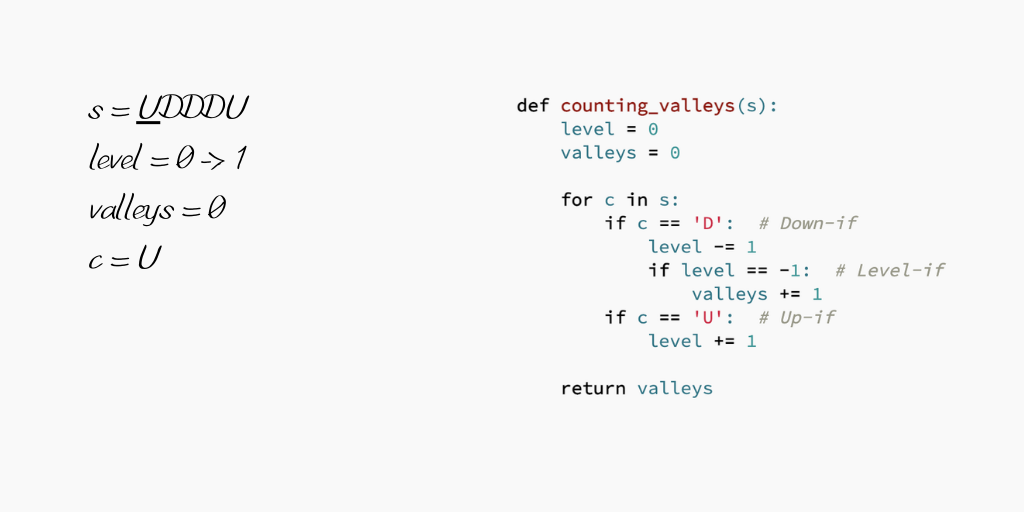

The condition in Down-if is False. Move to the Up-if. Condition is True. level is increased by one. level equals 1.

Next iteration.

c is equal D. Underline corresponding D in s

First if. The condition is True.

level is now equal 0

So condition level == -1 is False

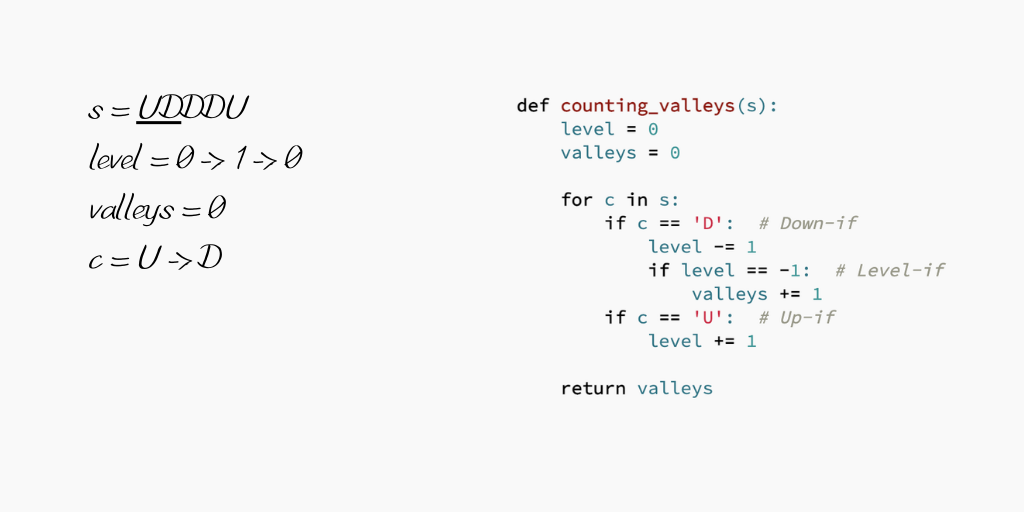

Next iteration.

Again c is equal D. Underline corresponding D in s

First if. The condition is True.

level is now equal -1

So condition level == -1 is True

valleys is now equals 1

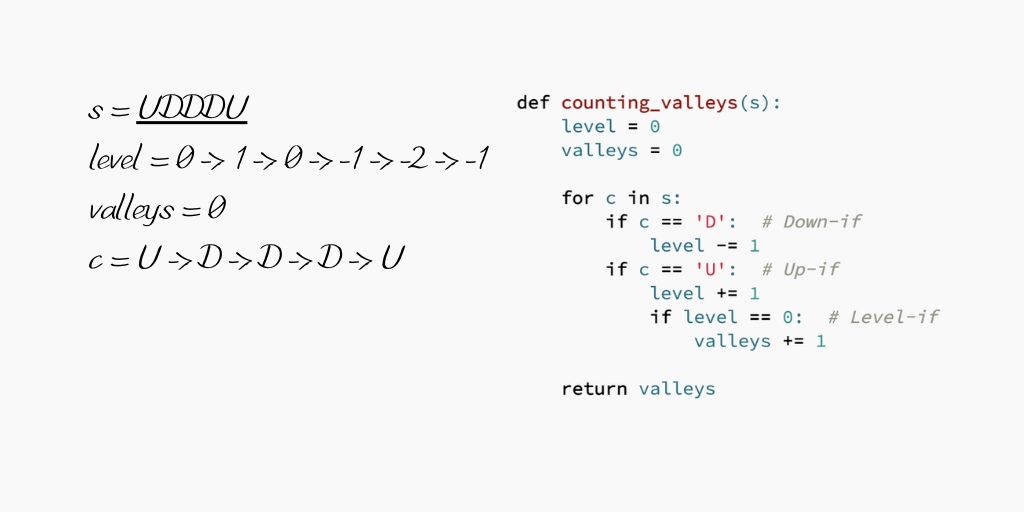

Hm… It looks like we have found a bug. So I will move the code Level-if block inside Up-if below increasing the level. And I will change the condition to level == 0

So this is my final code:

def counting_valleys(s):

level = 0

valleys = 0

for c in s:

if c == 'D': # Down-if

level -= 1

if c == 'U': # Up-if

level += 1

if level == 0: # Level-if

valleys += 1

return valleys

I've run the test case over it. My final state of the list of variables is:

I have checked this solution on HackRank. It is OK. All tests are green. As you can see it is much easier to follow me. We found a bug. Of course, it was an extremely simple problem. But with more complex problems this approach works even better. During the interview, it will help both an interviewer and you. Interviewers usually have the ideal - or what they think is the ideal - solution for a problem they give you. If you come up with a different solution, you have to prove that it works and it is good enough.

The main drawback of this approach is that it is very difficult to practice, at least for me. Usually, I use sites like Hackerank to find problems to solve. There is an online editor. It is so tempting to start code there. I prefer to start with pen and paper. I can decompose the problem easily. I can draw. I can write a couple of drafts. The next step could be finding some test cases… And debugging on that piece of paper.

But because I am a quite lazy person I switch back to the online editor too early. From time to time I even solve a problem in front of a computer from start to finish. It helps me to improve problem-solving skills, but it doesn’t help to improve interview skills.

If you are like me tend to do the same, I can suggest a trick that works for me more or less OK while I work on a problem from Hackerrank or a similar website.

- I write down significant parts of the problem using my own words.

- Write down all given test cases if there are any as a reference.

- I go to a quiet place without my laptop. This is the crucial part. Left the laptop away.

- Sit down there and solve the problem… with inventing my test cases, debugging, and if it is possible I do it out loud.

- And only if I have a solution, I return to my computer and type it in.

There is a mailing list called Daily Coding Problem. If you are OK without checking your solution with a set of tests online, using that list could be a good alternative. Or you can organize many interviews for yourself. It is rather easy to do.

To summarise the idea

Assume that your code has bugs. Assume that an interviewer has in mind a different solution for a problem. Assume that neither interviewer nor you can keep more than one state of one variable in memory. Write everything down. Every state, every variable of each variable you have in your code. And practice, practice, practice...

P.S. Does anybody can recommend a decent book for coding interview preparation? I know only Cracking the Coding Interview.

Got a question? Hit me on Twitter: avkorablev